In 1967, the year I was born, Americans saw some tough stuff: More than 11,000 US soldiers died in Vietnam, race riots broke out in half a dozen states, record blizzards and deadly tornadoes struck the Midwest, the Six-Day War gripped the Middle East, Segregationist Lester Maddux was sworn in as Governor of Georgia — you get the picture. Tumult.

Then came 1968. ‘Nuff said.

But amid all of that strife over those two years, a humble visionary from Illinois named Abner Mikva ran his first winning campaign for the US Congress — a political office that I would end up covering, managing, studying, and writing about for a quarter-century.

Abner Mikva was born in 1926 to a poor family in Milwaukee, Wisconsin — three years before the start of The Great Depression. During World War II he enlisted in the US Air Force and became a navigator. The war literally ended one day before he was scheduled to deploy. So, instead of shipping out, he ended up enrolling in the University of Wisconsin, courtesy of the G.I. Bill.

Having grown up in Illinois politics myself, I was already familiar with Abner Mikva’s legacy. But I recently learned a lot more about the man after watching my friend Bob Hercules’s superb PBS documentary: Mikva! Democracy is a Verb.

Early on in the film, Mikva tells the story of how he got his first direct dose of the infamous “Chicago Machine.” In 1948, as Adlai Stevenson was running for governor and Paul Douglas campaigned for the Senate, Mikva wanted to get involved. One night, he stopped in at the 8th Ward Democratic Headquarters and walked up to a craggy old Committeeman chomping on a cigar:

“I’d like to volunteer for Stevenson and Douglas.”

“Who sent ya?”

“Nobody sent me.”

“We don’t want nobody, nobody sent.”

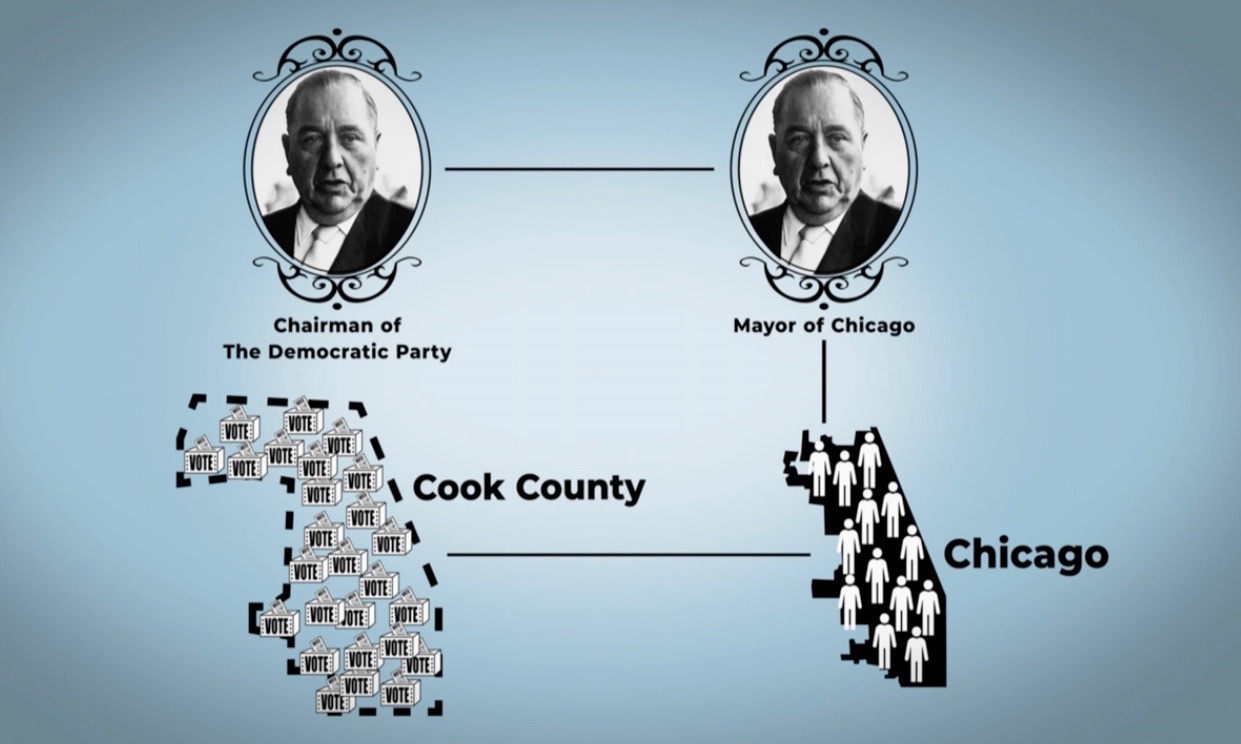

This was during the 1950s when Mayor Richard J. Daley ruled the Windy City with an iron fist. His Machine ran a patronage army, rewarding loyalists with city jobs — 40,000 of them. Daley could do this because he was both Mayor and Chairman of the Cook County Democratic Party.

Mikva’s first foray in standing up to Daley was running for the Illinois State Legislature under the banner of the nascent Independent Voters of Illinois (IVI). In 1956, he got elected at the age of 30 and immediately built a reputation as a legislator who could negotiate and build compromise with his Republican colleagues.

But he was fierce when he knew he needed to be. Right away, Mikva took on Daley by fighting against Chicago’s housing discrimination. He stood up again when the Mayor tried to put a steel mill and an airport in Lake Michigan. Mikva kept the pressure on Daley, consistently fighting for civil rights reforms, and slowly wore him down.

On his second run for Congress in 1967-68, the Mayor could see that Mikva was destined to beat the Democratic incumbent he had under his thumb. Daley remained neutral, and Mikva got elected.

In Congress, Mikva worked across party lines on an array of issues, but when it came to gun violence, he gave no quarter. His impassioned efforts to outlaw handguns made him the first high-profile, national target of the gun lobby. In 1979, when Mikva was nominated to be a federal judge on the powerful DC Court of Appeals, the NRA spent a record $1 million to oppose his appointment. It lost.

A decade later, Mikva had become the chief judge of the court, in time to write the opinion for one of the most controversial and consequential decisions of his career: Steffan v. Aspin. President Obama spoke about the case when he awarded Judge Mikva the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2014:

“In 1993, Abner struck down the Pentagon’s ban on gays in the military. He was overturned on that one, but history proved him right. And he inspired the next generation, including me.”

Mikva retired from government in 1995, after briefly serving as White House Counsel for President Clinton. Three years later, the Mikva Challenge was established as a tribute to him and his wife Zoe, a lifelong teacher and activist. The program motivates young people to get involved in elections and government — and provides them the access to do so. Twenty-five years later, with offices in Illinois, DC, and California, the Challenge reaches more than 50,000 kids across the country with its Action Civics curriculum.

One of Mikva Challenge’s alumni, Chris Butler, explained a few years later what the program had meant to him and so many others:

“Today, I’m a Mikva Challenge Board member, and at the Mikva Challenge, we help young people in high school to realize that we are somebody. That we do have a voice and a place in our democracy. Because of the Mikva Challenge, so many of us can dream bigger and reach higher than we ever thought we could.”

Serving in elected or appointed office in the federal government is not an easy place to make a big difference — on either side of the aisle — even under the best of circumstances. And our politics today are a long way from the best of circumstances. Of late, when friends ask me to “talk them off the ledge” about the state of our system, I don’t always have such a speedy answer. But one thing I do know is that it’s the Americans who are a lot younger than me who will be the key.

On my actual birthday, Thursday, Feb. 9, 1967, The New York Times printed the full text of President Johnson’s “Special Message to Congress on Children and Youth.” It had been read aloud on Capitol Hill the day before; an outline of LBJ’s specific goals to enhance support for children — especially in the areas of healthcare and education. Near the end of the president’s Special Message, he declared:

“We make this commitment to our youth not merely at the bidding of our conscience. It is practical wisdom. It is good economics. But, most important, as Franklin D. Roosevelt said 30 years ago, because ‘the destiny of American youth is the destiny of America.’”

President Johnson’s words are the very ethos of the Mikva Challenge.

I asked Hercules what his lasting impression about Mikva the man was after he made the film. Bob zeroed right in on the example that Mikva set:

“What I really gained is an appreciation for Ab’s lifelong advocacy for democracy, civic engagement, and his belief in young people to change the world. As we’ve seen with the recent assault on our Capitol, democracy is a verb: something we constantly have to fortify and nourish, else it dissipates in front of us.”

On the 4th of July, 2016, Abner Mikva died at the age of 90. Altogether, he had spent more than 40 years serving in American government. After all that time, it would have been easy for him to become jaded — to be subsumed by the “establishment.” But it never happened. Mikva always held firm to those righteous principles that first drove him when he was a young man standing up to the Daley machine.

At the end of the documentary, Hercules closes the circle in poetic fashion. The final quote comes from Congresswoman Jan Schakowsky (D-IL), who volunteered for Mikva as a young woman and who has now served for two decades in Congress. Beaming with pride, Schakowsky first throws a little shade at Daley, but then far more importantly, she pays perfect tribute to her dear friend Abner and the Mikva Challenge:

“Literally thousands of young people now are going to know that somebody did send them. I love that.”

Me, too. For they are the answer.