A melodramatic headline, to be sure. “Curing America” suggests that I’m about to deliver some grand, master plan that will solve an ingrained and seemingly intractable problem.

But it might be far less complex than it appears. Bear with me here. And be open to re-training a bit of your brain.

Freeing up one’s mind is not a complicated concept, but the actual doing of it can be very difficult. As human beings, we get conditioned to think in certain ways and to protect our own beliefs. To narrow our focus. Yet the fact remains that every American retains the capacity to figuratively put ourselves into anyone else’s shoes. To see things in a different way. And I submit to you that this is the most urgently missing ingredient in any effort to change the tone and track that our country is traveling down.

First, a disclaimer: If you happen to be someone who sincerely believes that America is in good shape — politically, electorally, relationally, spiritually — then the following prescription likely won’t have much meaning for you.

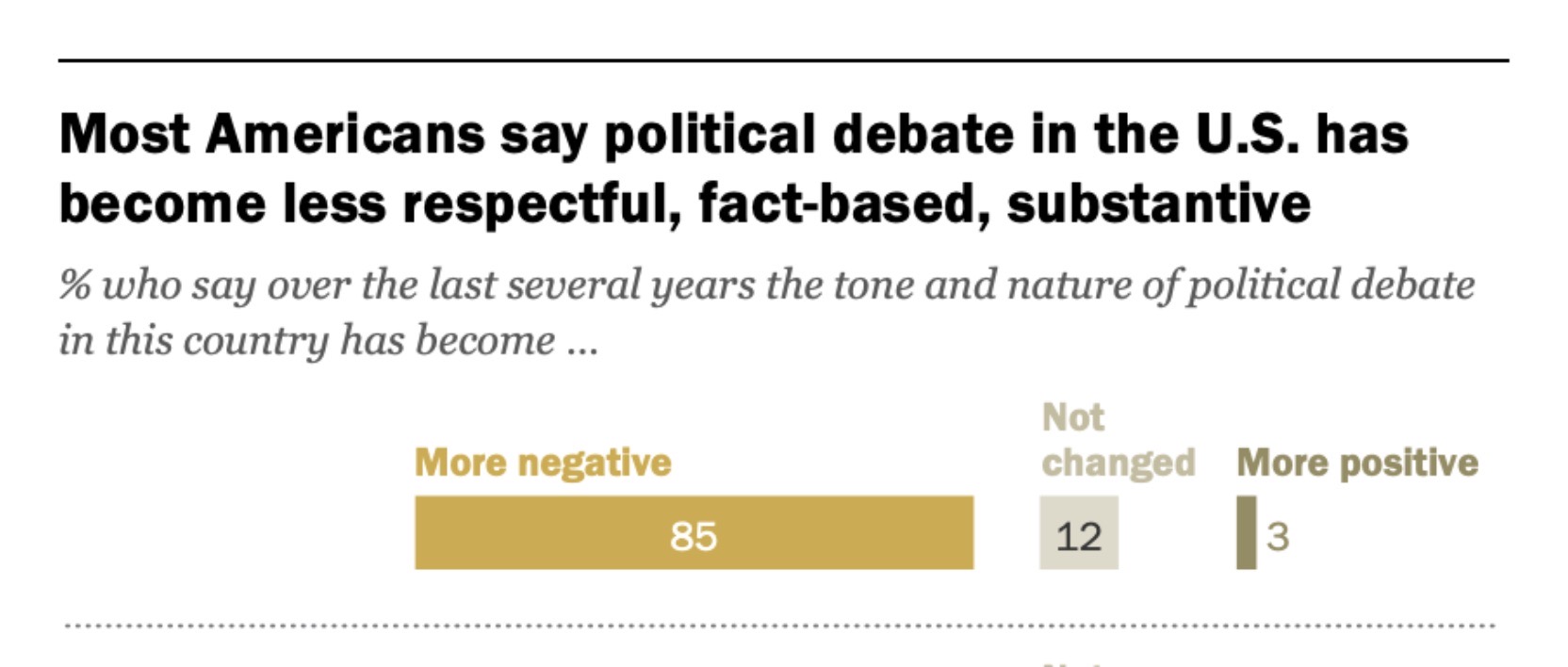

To be clear, that kind of favorable opinion is held by a stark minority. If you take the average of more than one hundred polls over the last 24 months — under equal-time of governance under two diametrically opposed political administrations — just 29.8 percent of Americans believe our country is heading down the right track. And even before the 2020 Election, 85 percent of Americans believed that our political discourse had become far more negative.

Polls ebb and flow, of course. And all of our individual experiences are limited to begin with. The perspectives we have about our country are shaped by a variety of factors: Geographic region, socioeconomic background, upbringing, education level, as well as the period of American history we’re living through. At 54 years of age, I have missed out on 75 percent of our country’s existence.

At the same time, nearly every person I know — no matter what their political bent or background — feels that America’s collective civic condition is mired in a downward spiral. Too much angst. Too much shouting. Too little listening. And as a consequence, not enough understanding. In fact, a glaring lack of it.

WE ARE THE KEY

Setting aside the negative impact that a lack of communication and understanding has when it’s occurring between the representatives we send to Washington — and I went deep into this in Unlock Congress — in a way, the disease starts with us.

I’m not talking about neighborliness or friendliness on a general level. Americans are a very giving people. And most of us don’t get up in the morning looking to get into a fight or violate our neighbor’s rights. We want to help where we can. Giving feels good. This concept is universal.

But the times when we see Americans come together in the most purely voluntary fashion — without judgment or partisan strain — is when a tragedy befalls a community. Immediately, the members of that town, city or state bind themselves closer together. They start rowing in the same direction.

The best example of this is the way in which victims of natural disasters close ranks. It happens the very minute after the event. And the reason, of course, is empathy: No matter what their previous differences, now every victim knows what it’s like to walk in their neighbors’ shoes — because they’ve been instantly placed into each other’s shoes. They don’t need to walk the proverbial mile in them — or even a single step. Their journey is already the same, as is their imperative: Fight for the lives they were living just moments ago.

A high profile example of this happened in New Jersey after Hurricane Sandy. When Bruce Springsteen embraced super-fan Chris Christie, he and we knew it was only because of the common pain they were feeling for their beloved Garden State. We knew this because Springsteen told Chrisite so. Without being in those same shoes, the singer and governor wouldn’t have come within safe COVID-distance of each other.

But without such an urgent reason for connection, it can be a whole lot harder for Americans to set aside or suppress their political differences.

Don’t get me wrong: This is not a naive, kumbaya plea for a suddenly halcyon American citizenry. And in no way am I suggesting people should change or even attenuate the energy they expend to achieve their own political ends.

As a guy who cut his political teeth running Democratic campaigns in Chicago, I doubt I’ll ever lose all of my partisan edge. But just because I donate, work for, or vote to elect a specific candidate or platform, it does not mean that I am robbed of my ability to listen to opposing viewpoints. More than listen to them — to hear them. Or at least to make an honest effort; to try to get to the place that drives another person’s thinking and that’s helped them to shape their opinion or ideology.

Or to at least make an honest effort. To try to get to the place that’s driving another person’s thinking; that’s helped them to shape their opinion or ideology.

This doesn’t mean I have to agree. Listening to other viewpoints and then working to advance your own are not mutually exclusive. The same goes for practicing hardball politics; it never precludes you from listening.

Elections are won through votes, dollars, and activism on the ground — not raw anger. Protracted yelling matches laced with profanities where neither side is listening achieves nothing of value. What it does do is add to the toxicity.

Joseph Zompetti, a professor at Illinois State University, wrote an entire book on the difficulty and importance of changing the way we talk about politics. The author of Divisive Discourse distills it down:

“Don’t enter these conversations as a competition or trying to win a debate. The other person is a human being and they’re not always wrong and you’re not always right.”

I put this tactic into practice a few weeks ago and then wrote about it. In “My QAnon Date,” I recounted a conversation where I decided to calmly ask a woman questions about her beliefs — instead of reflexively lecturing her about why I thought those beliefs were ridiculous.

I may have missed the mark with a couple of readers. Their responses went along the lines of: “How could you ever get through that dinner? How could you stand it?” The answer is simple: Once you let your curiosity move ahead of your ego, the results can be fascinating. Not to mention far more productive. Plus, the Tagliatelle was awesome.

I’ll likely never see that person again and it’s almost a guarantee that we won’t vote for the same candidates. But just listening to her taught me something about the seeds of a movement that I find incredibly dangerous.

There’s no shortage of highly charged debates in our political culture to test this theory on. Some are so fraught — abortion and guns come to mind — that the media often has to go through a pained process even to explain how they refer to an issue.

In just mentioning those last two issues, I may have lost a couple of readers. How dare I say that there are two sides to every argument! Even the ones where there are many millions of believers on both sides. And that’s the problem: Our passions, no matter how well-intentioned, often prevent us from freeing our minds to consider other viewpoints.

The most telling statistics I’ve ever come across that describe the hypocrisy and biases that so many Americans hold about what’s acceptable speech — on both sides of the aisle — was in a 2019 Pew Research survey. While 75 percent of us believe that heated rhetoric leads to more political violence, Pew reports that Americans have very different ideas about who can say what:

“While most Democrats (78%) say it is very important for Republican elected officials to treat Democratic officials with respect, only about half (47%) say it is very important for officials from their party to treat Republican politicians with respect. There is similar divide in the opinions of Republicans: 75% say Democrats should be respectful of GOP officials, while only 49% say the same about Republicans’ treatment of Democratic officials.”

Digging out from under this deep-seated level of partiality is a daunting challenge — yet an essential one.

THINK LIKE A JURY

Americans who sit on jury trials fulfill their civic and legal duty if they objectively apply the law from the beginning of opening statements to the end of deliberations. In other words, they have to try to free their minds.

Weighing a case depends on the evidence presented and whether a reasonable standard of guilt can be established. And when a criminal case involves two or more individuals where their behavior is under examination, often jurors have to imagine what it was like for the plaintiff and the defendant in the very same moment.

To do their jobs correctly, jurors must crowd out many of their preconceived notions and focus on the facts and the law. In many cases, they are required to try to determine the participants’ states of mind. What might they have reasonably been thinking? Or anticipating? Or trained to do — or not to do? Where was their head?

When a guilty verdict is handed down in a trial, it does not mean that it’s correct. Same for not guilty. It means 12 jurors did their best and agreed upon a verdict.

But once there is a consensus that a trial has been properly conducted, there is an assumption that the members of the jury looked at the case from every possible angle. That they listened to the facts and the arguments and tested the logic and veracity of each. That they freed their minds and treated the opposing parties fairly; they didn’t just make a snap decision based on their own perspective. They tried to get out of their own shoes.

Very often there are nuances in testimony presented at trials. Some things are true. Some things are partially true. Some things are false — and some things don’t fall neatly into one category. This is nuance. If there wasn’t any nuance, juries would all return their verdicts in under 60 seconds.

But life is messy. It’s complicated. And the same can be said for so many of the political issues that Americans disagree on daily. It’s perfectly healthy to stake out a firm position on anything you believe in. It is not healthy to reflexively state that the opposing side has no merit whatsoever — unless you’ve investigated the facts first.

Nearly a century ago, F. Scott Fitzgerald famously wrote:

“The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.”

I love that quote. My only qualm with Fitzgerald’s assertion — and I dearly hope I’m right about this — is that being contemplative of opposing ideas does not require any minimum floor of intelligence. It takes discipline. It takes a little re-train of the brain. And that’s exactly what jurors are compelled to do.

Practice certainly helps in this process, for discipline comes from practice. But anyone can accomplish this type of thinking if they have the will to do so. And in no way does it prohibit a person from formulating their own final opinion on any matter.

A TIME TO FEEL

Movies have always been a great way to take someone’s mind on a trip and show them a perspective or experience that may serve to change their thinking. Or at least have the effect of expanding their aperture to see an event or idea through from more than one point of view.

Films like these are often called “morality plays.” When a movie is about war or power or race or corruption or any other theme where the question being considered is not an open-and-shut case, it can prod us into confronting our own belief systems or the prisms through which we see things.

A Time To Kill falls into this genre. Twenty-five years after its release, it’s still a movie that stands out in my mind. Not because it was a great film; even John Grisham, who wrote the novel, called the final product merely “good.” I love it because the final courtroom scene is one of the most cleverly dramatic that I’ve ever seen.

In A Time To Kill, Samuel L. Jackson plays a father in the Deep South whose 10-year-old daughter is brutally raped and beaten by two young white men. After they get arrested, Jackson takes the law into his own hands and shoots them dead while they’re being walked through the courthouse. Now Jackson faces trial for murder.

Instead of accepting the NAACP’s offer to defend him, Jackson hires a conservative white lawyer played by Matthew McConaughey. Near the end of the trial, McConaughey knows that he’s losing the case. The audience thinks the same, because we get to see the all-white jury saying a few things outside of the courtroom.

The night before closing arguments, in his jail cell, Jackson explains to McConaughey that the only reason he picked him was because he’s white. He tells him that he’s his “secret weapon,” because McConaughey sees him first as a Black man — just as the members of the jury do. Based on this, Jackson offers his attorney some strategic advice:

“Throw out your points of law, Jake. If you was on that jury, what would it take to convince you to set me free. That’s how you save my ass. That’s how you save us both.”

McConaughey’s character finally gets it. In his closing argument, he first asks the jury to close their eyes. Then he tells them to listen to him — and listen to themselves. Then he proceeds to slowly review in gruesome detail how Jackson’s little girl was brutalized. When he’s done, he looks at the close-eyed jury and slowly asks them through his own tears:

“Can you see her? Her raped, beaten, broken body, soaked in their urine, soaked in their semen, soaked in her blood, left to die. Can you see her? I want you to picture that little girl (long pause)…Now imagine she’s white. The defense rests, your honor.”

At that moment, every person in the courtroom opens their eyes — but most of them in a whole new way. And the expressions on the faces of the jury tell the tale. McConaughey’s flipping of the script forced every juror to really imagine what it must have felt like to be in Jackson’s shoes and carrying his broken heart. The alleged crime hadn’t changed. The facts hadn’t changed. But the jurors’ lenses had changed.

In a truly famous film, To Kill A Mockingbird, Atticus Finch boiled this principle down in the two sentences of advice he gives to his nine-year-old girl:

“If you can learn a simple trick, Scout, you’ll get along a lot better with all kinds of folks. You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view, until you climb inside of his skin and walk around in it.”

In the next sentence, Finch starts to explain the concept of “compromise.”

COMPROMISE

For my money, compromise is one of the most important words in the English language. I can’t think of a single type of positive human relationship that doesn’t require it. Perhaps marriage above all.

So very often, the impediment to two parties reaching compromise is being unable to see the other side of the equation. To try to understand and even feel the other stakeholder’s pain or need.

The same goes for the art of persuasion. If you’re trying to convince someone to change their mind — or even move toward middle ground — shaming or mocking them for their beliefs does not work. Why would it? Instead, maybe try understanding where they’re coming from.

In 2015, researchers Robb Willer and Matthew Feinberg at the University of Toronto ran a study comparing the effectiveness of political persuasion across six issues when the persuader’s argument is based on his own moral beliefs — versus making an argument that incorporates the values of the opposing viewpoint. It made a big difference.

For example, conservatives were more likely to favor universal health care when they heard that more uninsured Americans might increase the spread of disease. And the study showed that liberals’ support for higher military spending ticked up when they listened to an argument explaining that employment opportunities in the military branches help to decrease inequality. Professor Feinberg summed it up in practical terms:

“Instead of alienating the other side and just repeating your own sense of morality, start thinking about how your political opposition thinks and see if you can frame messages that fit with that thought process.”

Pretty logical stuff.

Long before the COVID-19 epidemic, the American Academy of Pediatrics conducted studies in 2006 and 2013 to address the challenge doctors were facing in having parents vaccinate their children. The studies found that when pediatricians took the approach of listening to parental concerns and patiently providing the necessary information, anywhere from a third to 50 percent of parents changed their minds.

In 2017, researchers at the Washington of University of Medicine in St. Louis ran a similar study. They came to the conclusion that the best way to overcome standoffs over vaccinations was “having doctors listen to — not shun — reluctant parents.”

No matter where you stand on the issue of vaccines, the point of these examples is the power of listening versus lecturing.

Of course, being thoughtful and civil in any dialogue is also dependent upon the party with whom you’re communicating. If a person is too angry, or worse, committed to dangerous acts of extremism, then there is no exchange to be had. When any individual begins to inflict damage upon others, they risk forfeiting their right to be heard. At least until trial.

But it’s good to keep in mind that there is almost always a reason why a person has chosen to adopt a dangerously radical course of behavior. This is not an excuse; it’s just a reality. And it’s also a fact that the ways in which people are sending and receiving information in our society can be the very bridge that takes them to the brink.

THE MODERN MEDIA MONSTER

I’ll never forget a phone conversation I had seven years ago with a legislative aide on Capitol Hill. He was helping me to obtain some research as I was finishing up the first draft of Unlock Congress. He’d seen the book’s framework, and as we were about to hang up, he volunteered his own opinion:

“Michael, I think the reform ideas you have in there are great. But frankly, I’m more worried about the poisonous media atmosphere. Especially with social now. It makes everything that much harder to do around here, and it’s a genie that you just can’t put back into the bottle.”

The reason I remember it so vividly is that I agreed with him — and I was already concerned about the fact that I wasn’t including it in the book. I couldn’t, really, because it’s a whole other subject. But as a guy who worked in print and broadcast news and then politics for 20 years, I knew all too well the power of a media world that’s been accelerating at the speed of light.

There’s no question that cable “news” and social media can add up to a terrible abyss of negativity and attack. If it all happened in a vacuum, it wouldn’t be so treacherous. But when it has the effect of increasing the political vitriol amongst and between Americans, the consequences can — and have been — disastrous.

But if you take a step back and look at media content just from a raw level of curiosity, it’s actually another opportunity to see what the other side thinks — and why.

I confess that I consume too much of this stuff. It’s not the best use of time; especially since I find all of the national cable outlets to be way over- the-top — regardless of their political bent. And they all have one.

At the same time, I’ve learned to watch the network I disagree with the most without letting it get my blood up. I try to find points on which I agree with, and then I try to examine other assertions with a critical but empathic eye. There are hosts that I find disgusting — and yet frequently I find the cases that they’re prosecuting on-air to be fascinating.

For my part, it helps that I’ve had a career that’s allowed me to meet and work with all kinds of people. It also helps that I’ve lived in seven different states, most recently Illinois and Arizona. My spectrum of friends and adversaries runs the political gamut. Yet even with an open mind, I still have to make an effort to absorb perspectives I disagree with — without getting defensive.

When it comes to consuming all of the media content you come across — including the words you’re reading right now — it’s important to remember that that’s just what they are: words. And a lot of times, the heated language flowing through the pipeline has its own profit motive. It doesn’t all have to be taken so seriously.

Again, votes decide elections. And notwithstanding the serious battle going on over our election systems, it is still our own actions that move the needle. As Professor Feinberg explained, almost channeling Sun Tzu: Knowing thy opponent is one of the keys to achieving victory. It has ever been thus.

When you listen to political perspectives that are different from your own, the people who hold those views feel heard. When anyone feels that they have truly been heard, it’s a step away from division, and closer to connection. Any strategic learning one might also take away from such an exchange is just a bonus.

THIS STUFF AIN’T EASY

To say that I’m some master of this process of listening without overreacting would be false. But I’m always trying to get better at it. Because I truly believe in the words Alexis de Tocqueville wrote in Democracy in America nearly two centuries ago:

“The health of a democratic society may be measured by the quality of functions performed by public citizens.”

Those “functions” include our discourse with each other as well as our treatment of one another. The whole of America is still far bigger than the sum of its parts. But not if the parts are so defective that they are unable to congeal into a whole of any substance.

We are the parts.

Please bear in mind that the words “easy” and “quick” are nowhere to be found in this article’s headline. There is no question that moving to this level of contemplation and temperament is terribly hard to achieve.

But outside of some quixotic prospect of a “benevolent dictator” who waves a wand and somehow delivers a utopian vision for our collective future — representative democracy is still the default system in the United States. A historic one, no less. But without a baseline level of trust in each other, our tainted system will fray only further. An angry country is always on the edge.

The road back always starts with the individual. Our own behavior. What we think, what we say, and what we do. It all adds up. And it’s all within our control.

Is this approach, in fact, the cure for America? Of course I can’t say with a straight face that it is the only answer. But I do believe without question that the way we speak, listen to, and treat each other is undoubtedly a large part of the solution.

You may say: “OK, Golden. Put your money where your mouth is. You say you managed Democrats — tomorrow is January 6th. If violence breaks out again in the public square, you still gonna listen to what the ‘other side’ has to say?”

Fair. Here’s the answer: If the people I’m talking with aren’t breaking any laws or hurting any other folks — you bet I’ll listen. Open door.

The process of curing America starts with each one of us.