The “George Floyd Justice in Policing Act” sits in front of the US Congress at this moment. Among other things, it would strengthen prohibitions on discriminatory police behavior and officers’ use of excessive force.

Policy changes do not happen automatically after tragic injustices. Far from it. But sometimes they do. And there’s one that is etched into my memory.

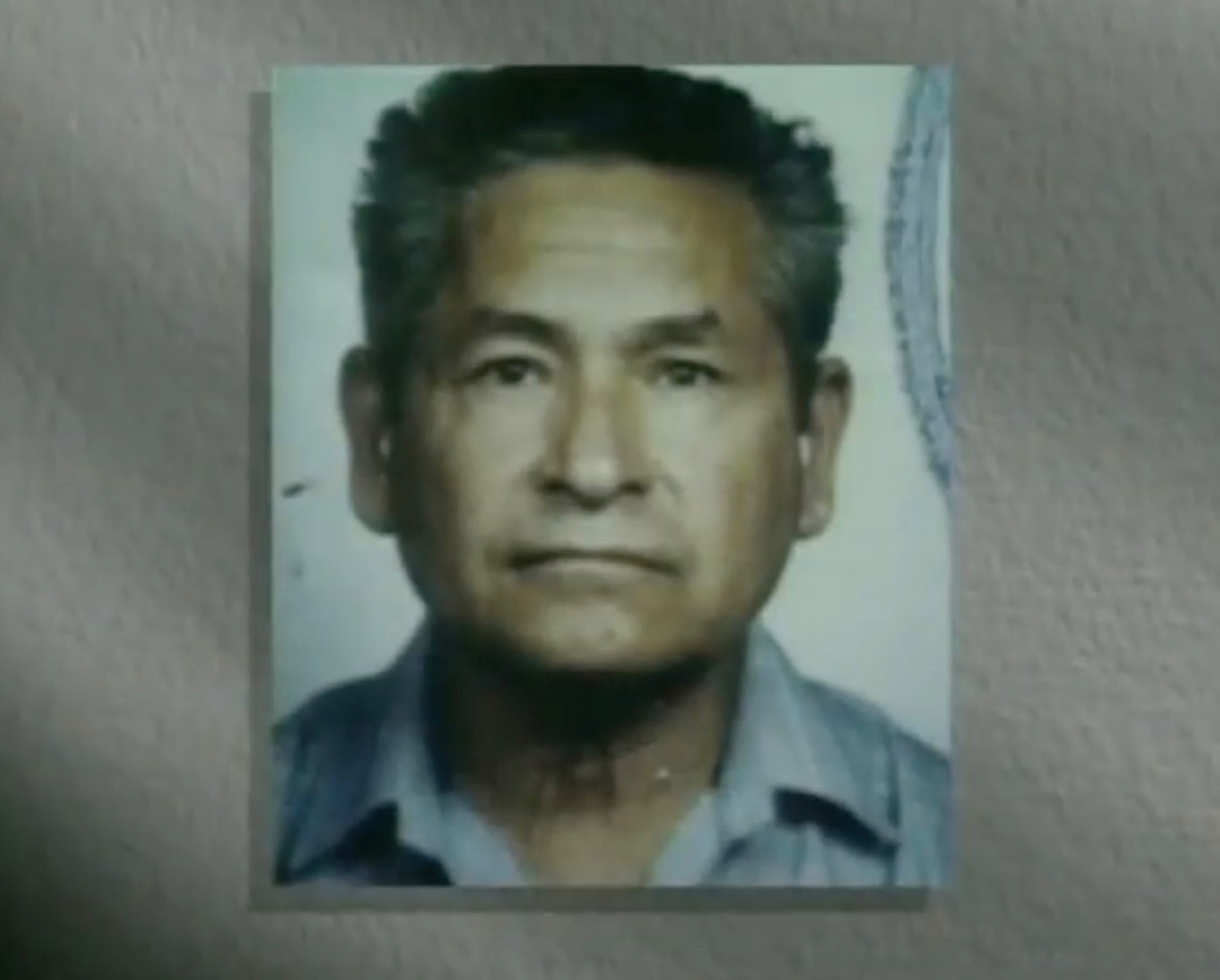

Early on a July morning in 1997, just after 7am, a 64-year-old man named Ramon Gallardo and his wife Carmen were asleep in their bed. The next minute, police officers entered the room and shot Mr. Gallardo 15 times with MP5 submachine guns.

This all happened in the sleepy farm town of Dinuba, California. Population: 15,000.

Fifteen officers who comprised a SWAT-like “Special Enforcement Team” were executing a search warrant. They’d heard that a gun involved in a gang shooting outside Dinuba was illegally sold to one of the 13 Gallardo children, who all lived with their parents.

No guns were found in the house, and the informant would eventually recant the false tip.

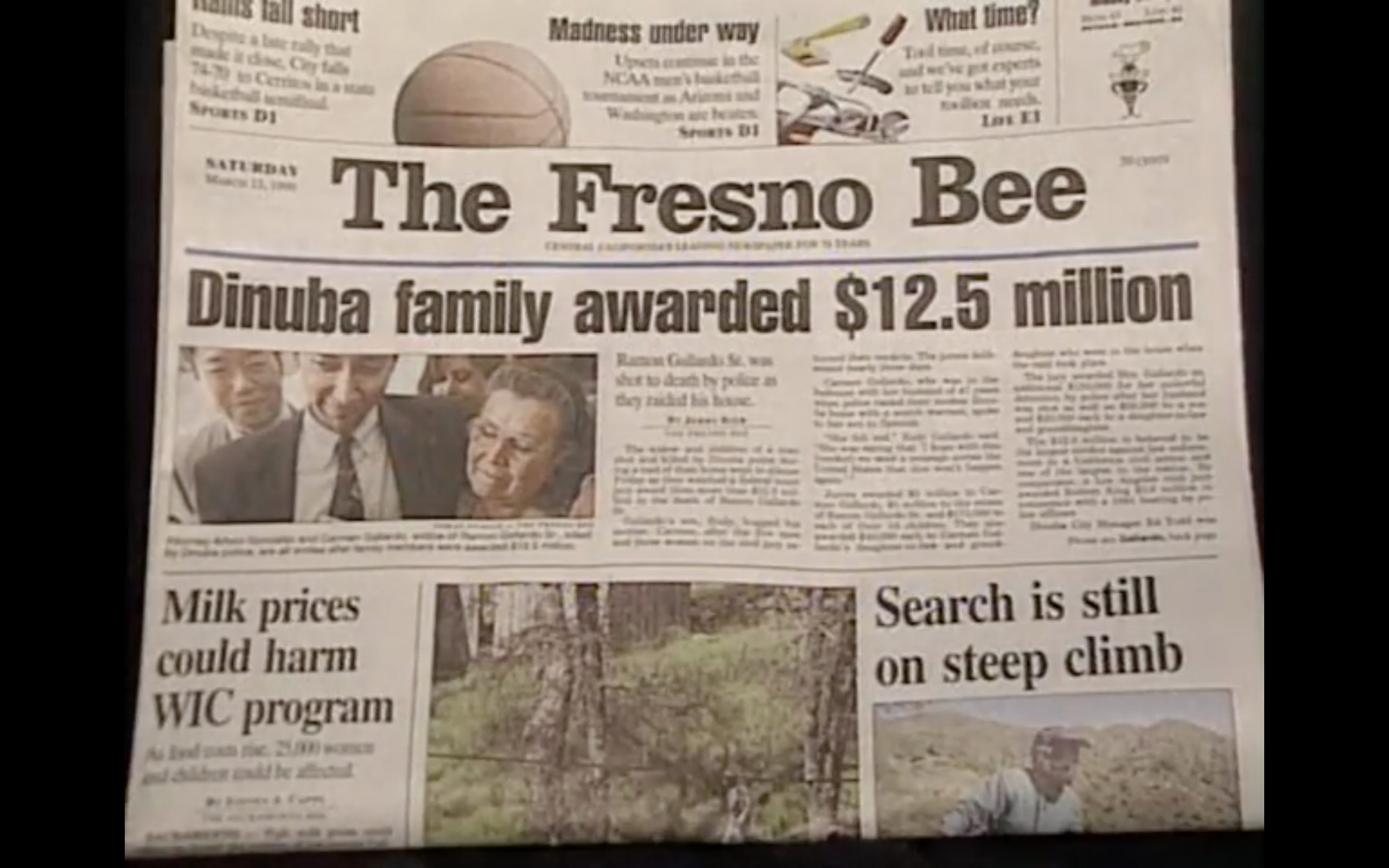

I will never forget this case, because I reported on the aftermath of the shooting and the civil trial in federal court which produced the largest jury award in the history of California: $12.5 million.

When I interviewed the Dinuba Police Chief shortly after the shooting, he claimed that Mr. Gallardo had been moving toward the officers with a knife and had been told to stop in both Spanish and English.

There was a video in this case, but it was taken from atop one of the squad cars outside the Gallardo home (they did not have body cameras at the time). Authorities refused to release the squad video. Unlike today, most official videos were not offered up for public consumption in the 1990s.

The video was eventually leaked to me to air on the NBC-TV station I was working for — but not until after the trial had concluded. The jury did not have to wait that long to see it.

An uber-confident attorney named Arturo Gonzalez had represented the Gallardo family in federal court. He was a 38-year-old Harvard-educated lawyer who was also the child of migrant farm workers. He took a lot of cases at the time that his colleagues just wouldn’t touch.

The case played out in a federal courtroom, so I was not permitted to have a camera inside. But I remember the exact moment when the jury and I first watched that videotape. And heard it.

What we saw was an officer in tactical gear kneeling in the driveway. What we heard first was a barrage of machine gun shots being fired at Mr. Gallardo (watch here at 40:28). Officers yelled: “Shots fired, shots fired!” A few seconds go by, and then another barrage of bullets.

Gonzalez confidently and methodically made the case that the SET unit was completely unqualified for its purpose that morning. He explained that the unit had only been assembled three months before the raid on the Gallardo home — and that they had only practiced three times.

Step by step, Gonzalez convinced the jury that the SET enforcement action was unlawful under the U.S. Constitution. The verdict came back that the officers had entered unlawfully and used excessive force (violations of the 4th Amendment) and as a result, had caused the wrongful death of Mr. Gallardo (14th Amendment).

In an interview outside the courthouse following the verdict, Gonzalez tied it all together for the cameras:

“These officers simply were not well trained… The D.A. from Tulare County conducted a bogus investigation and came back and said these officers had done nothing wrong. Nothing wrong! And yet this jury has found that they violated the Constitution three separate ways! Somebody has got to explain that.”

The record $12.5 million jury was its own headline in the case. But perhaps more importantly, the city of Dinuba officially outlawed the use of SWAT teams in its policing.

When I spoke with the Dinuba City Manager, Ed Todd, about the change, he would not specifically talk about the verdict in the Gallardo shooting. Instead, he said:

“It’s just not a function that’s suitable for this size of a community. And I think we all recognize that.”

Twenty-five years later, multiple cases are being tried right now regarding police conduct. Protests fill the streets. People are making themselves heard.

The verdicts in these jury trials and also in courts of public opinion matter. Enormously. Not just to deliver essential justice to the victims. But also to change policy.

To change the law.