Twenty years ago, when I went to work for the Anti-Defamation League, I was just as excited to fight discrimination suffered by people of color as I was to battle the scourge of anti-Semitism. From the ADL’s Chicago office, I wrote and spoke out against hatred and racial discrimination in newspapers and venues throughout the Midwest.

But that didn’t subtract from the fact that I enjoyed white privilege. And no matter what I do or say, that privilege never goes away.

One of the best examples of this was my first reaction to Colin Kaepernick’s early protests.

Back then, a friend of mine named Michael Oberman asked me how I’d felt about the first few games of Kaepernick’s kneeling. A progressive like me, he was pretty surprised by my answer, since he knew the ways in which I’d spent my career.

At the time, I hadn’t written anything about the subject. I didn’t think it was my place to publicly tell Kaepernick or anyone else how they should or shouldn’t protest. As an American, he holds the same precious constitutional right as everyone else to use his voice as he pleases.

I told Michael that I respected Kaepernick’s right to protest, but that I would have preferred it to be in another venue than during the anthem. Perhaps leading player walkouts or large public protests.

Michael was so puzzled during that first exchange: If I was in favor of all of those other kinds of protests, and I’d been loudly speaking out against systemic racism for years, why the hell would I care about an activist kneeling during the anthem?

I told him that there was something about those couple of minutes that I’d always felt was special. Somehow I felt sentimental about putting my hand over my heart and singing that song in my painfully off-pitch voice. I told Michael that I do this no matter how much I am disappointed by our country’s deficiencies (and I wrote a whole book about it).

Michael pressed me on the issue — he’s a pretty fierce intellectual. He knew that I fully realized the righteous intent of Colin Kaepernick’s stand, so he wondered why I was so hung up on the symbolism.

I said that while I believed that there were plenty of military families who would not be offended by the protest — and would feel that this is exactly what their kids fought for — I also thought that many might be. I expressed that if I had had a child who’d died in battle, I think I’d be upset to see a protest during the one moment where it’s customary for all of us to stand in unison.

White privilege.

I think part of my blind allegiance to the anthem and military families stemmed from my acute awareness that I had never served in uniform, much less in a war zone. So I usually knee-jerk to elevating US veterans above all else.

But it’s still an expression of privilege. For it neglects to properly value the suffering and sacrifice of Black Americans that’s all happened underneath the very same banner that I’m paying tribute to.

My friend Jack Noldon put it more starkly. A 74-year-old African-American who served in Vietnam and then went on to a successful career as a news anchor in California, he said what should have been obvious to me in the first place:

“I know of many others who focus on the symbol and not on what the symbol stands for. In that one moment where it’s customary for all of us to stand in unison — we are not in unison. To force Colin Kaepernick or anyone else to conform to such a custom is coercion and majority tyranny.”

Notwithstanding the fact that I wasn’t forcing anyone to do anything, Jack’s underlying point is absolutely correct. And as obvious as it should be, he and I talked about how I will never fully understand it because I have not personally experienced it — not discrimination based on the color of my skin.

My friend Jarrett Adams put an even finer point on it. Jarrett is a 39-year-old African-American who was wrongly convicted and incarcerated at the age of 19. He learned the law in prison and eventually exonerated himself — then became a civil rights attorney. And one of my heroes.

Jarrett read a draft of this article and told me that it was “strong and to the point.” But I could tell that he was holding back. When I asked him to hit me with the raw, here’s how he replied:

“You may want to mention that Blacks who fought in the same war (WWII) were not given access to the GI bill, yet still there is a thought to stand for the flag. You covered this when you referenced Jack’s comment, but the fact that it didn’t come to mind, again, is white privilege. The privilege is that your conscience never even considers discrimination because it’s not a lived experience.”

Boom.

Jarrett’s answer reminded me of the time many years ago when I was arrested by Chicago Police officers. I was booked and placed into a cell at the notoriously seedy (and now defunct) Maxwell Street station. The cops weren’t exactly all smiles that night, but they treated me okay.

I can’t quantify exactly how much of that treatment was due to the fact that I was white. But what do know is that because I was white, my life was never in danger.

Black Americans are the ones who face that type of danger — all the time. Every damn day. Whether by rogue police or by your garden variety racist jerk, every day in America there is the potential that they will have to confront it. It just keeps going on and on.

And I will never know what that feels like.

Reni Eddo-Lodge, an authority and author on racism, defines white privilege this way:

“An absence of the consequences of racism. An absence of structural discrimination, an absence of your race being viewed as a problem first and foremost.”

Certainly, this is true, but I realize that it is much more than that. It’s never forgetting that every last reasonable option to fight discrimination must be embraced. Immediately.

I called Michael recently and told him that in the months after Colin Kaepernick’s early protests, I’d come to deeply respect what he was doing and that my admiration for him had only grown. I also told him that the months it took me to change my mind were a clear representation of my white privilege.

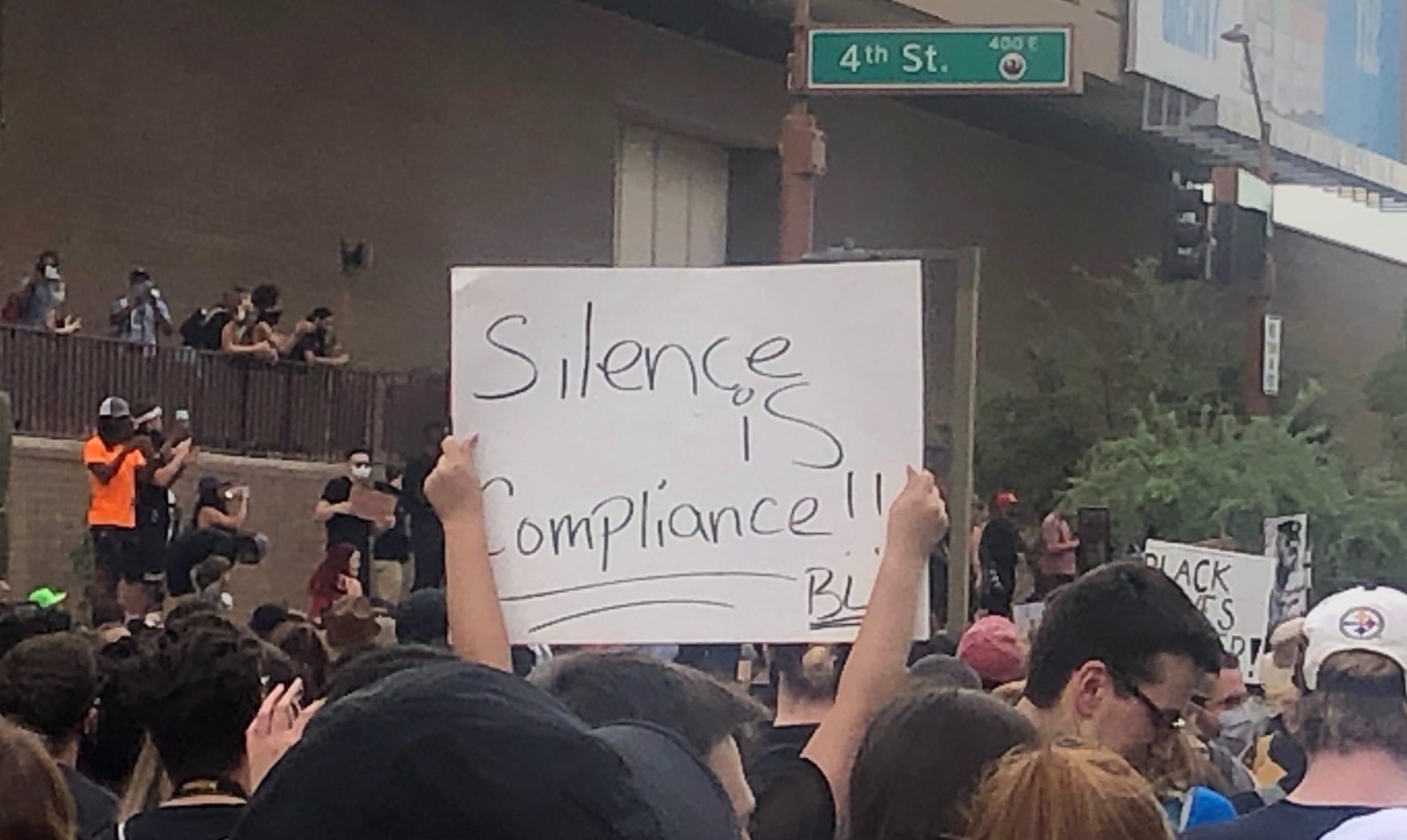

I was thinking about all of this when I took part in one of the marches last week. It’s so damn easy to go to a mass protest. It is marathons more difficult to stand alone in the public square and take the lead — regardless of personal cost.

I know that I’ll keep trying to do the kind of work that creates opportunity in order to increase equality — and that includes pushing for desperately overdue policy changes.

But just as importantly, I know that I’ll always keep learning new lessons about my own white privilege. A privilege that’s impossible to fully grasp in the same way that African-Americans do — because they are forced to live the other side of it. Every single day.

That’s why I believe it’s on me to keep all of this in the forefront of my mind. To be vigilant. Not just when I become infuriated by the latest or most visible racial injustices. But every single day.