Yesterday, a melee broke out during a US Senate “markup” session over a voting rights bill known as the For The People Act.

The partisan brawl was predictable enough. But the last thing I expected was to hear a GOP senator calling the bill “Jim Crow, 2.0.”

Ordinarily, I refuse to write about Ted Cruz. He says indescribably offensive/stupid things on a regular basis, and there aren’t really many un-transgressed taboos that remain on Capitol Hill. But Cruz’s disgusting references in the hearing and on Twitter also offer an opportunity to review an important piece of American history — and its relevance today.

What’s drawing the most attention right now in the For The People Act are the provisions that would make it easier for Americans to legally participate in elections. Cruz, with a straight face, was making the specious and ridiculous argument that because so many votes would be cast “illegally by illegal immigrants” if the bill becomes law (empirically untrue), Democrats would actually be reducing the value of Republican votes. Therefore, “Jim Crow, 2.0.”

For a guy who gets compliments on his brainpower, it was an incredibly feeble effort at rhetorical ju-jitsu. But it also made me wonder just how much the senator actually knows about the true origins of Jim Crow. Or any senator for that matter. Or white Americans in general.

A couple of years ago, Wesley Morris brilliantly summarized this history while guest-hosting the podcast series “1619.” A Pulitzer-winning writer, Morris takes the listener on a journey that starts with him in a friend’s kitchen listening to 1970s hits on “Yacht Rock Radio” — expressing his own pride in the Black roots that still run through America’s pop music — and then tracing them all the way back to their painful birth.

Morris tells the story of Thomas Dartmouth Rice, a struggling white actor who was performing from town to town around 1830. Rice happened upon a property where he observed an old Black stablehand cleaning a horse. The man was singing and moving rhythmically as he worked. And Rice was mesmerized by it.

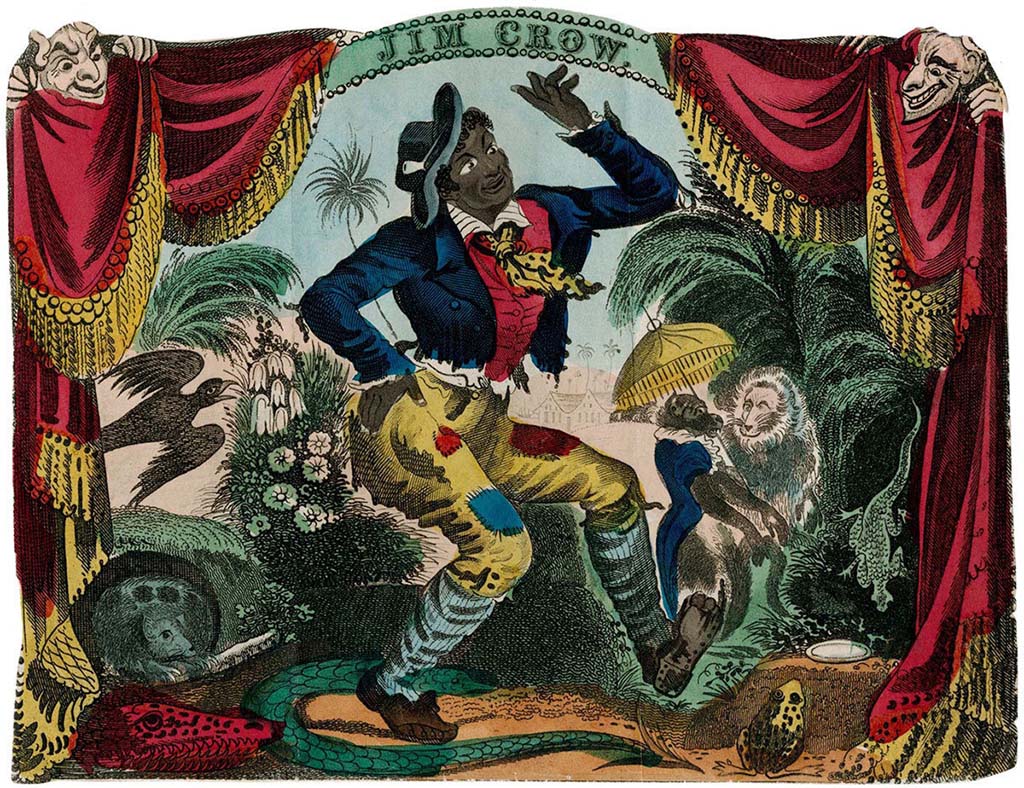

Rice took the harmony of the song and put his own lyrics to it. He created a buffoonish Black character that he named after the man who actually owned the property: Crow.

T.D. Rice may not have been the first entertainer to perform in Blackface, but when he broke out his new act, it exploded. White audiences went nuts for it.

It didn’t matter that Rice stole the content and then added his own dehumanizing twists to it — this was the age of slavery. “Jump Jim Crow” became a massive hit, and it turned minstrel shows into the main popular art form in America for decades to come. As those years passed, Rice’s terribly demeaning caricature of Blacks became deeper and deeper ingrained into America’s collective conscience.

By 1837, the term “Jim Crow” was being commonly used to describe racial segregation in Vermont. The rest is brutal history. State after state began to pass and enforce “Jim Crow” laws that institutionalized systemic racism in America.

Legal and illegal discrimination of Black Americans flourished for more than a century under the Jim Crow banner. And while passage of the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts of the 1960s were landmark achievements, we know that they far from settled the matter.

Moreover, the legacy of how whites viewed “Jumping Jim Crow” lives on to this day. A friend of mine, Jack Noldon, describes it as the original “Big Lie.” Long before Election 2020.

Jack is a 75-year-old Black American who served in combat in Vietnam before going on to a successful career as a journalist. He draws a straight line from the beginning of Jim Crow to the efforts and insults we see today from people like Cruz:

“The lie is that Black people are stupid caricatures of human beings who are child-like and buffoonish. That they are to be laughed at but never taken seriously, and must never be allowed to vote and must be controlled by force. This allowed whites to enjoy ‘the show’ while terrorizing the subject of ‘the show’ with horrible violence and repression. Today we have a new Big Lie, that the 2020 election was stolen because black and brown people were allowed to vote in large numbers and they cheated. And unless controlled by force, these cheating non-legitimate voters will dominate the nation’s politics and replace real (white) Americans — and pay back the real Americans in kind.”

For the last few months, I’d considered writing about the story of Jim Crow because of what I’d been hearing a lot of progressive voices — Black and white — referring to as “Jim Crow, 2.0.” Unlike Daddy Cruz, they were using the term in a proprietary fashion; as an extension of the righteous fights of the 1960s. Voting rights advocates were using it to fight back against the more than 360 voting restriction provisions that have now been introduced in states across the country (97 alone have been presented in Texas, Georgia and Arizona).

I could see why they were calling it “Jim Crow, 2.0.” But it still seemed like the term was being thrown around far too loosely. Making it solely about voting rights leaves out a ton of violent and deadly history suffered by Black Americans.

Cruz’s moronic comment sent me over the edge, to be sure. But I still felt hesitant to write about the history of Jim Crow — because it’s not my history.

Then I remembered something WNBA star Natasha Cloud said recently about this historical moment that we’re all living in. Last year, as the protests were gaining momentum, Cloud had made the hard decision to forgo the playing season in order to fully focus her time and energy on organizing in her hometown of Philadelphia.

In the new documentary “The Day Sports Stood Still,” Cloud sounded this note of optimism:

“You’re at these marches, and I’m getting chills right now just thinking about it. You see that there’s a lot of bad in this world, but there’s a lot of good people still here. And they’re not only Black, they’re every color. And they’re standing beside me, they’re fighting for me. They’re using their white voices, they’re using their privilege. They’re having hard conversations and dialogues about something that they don’t truly understand but they can be sympathetic to. That’s the beautiful thing about it and that’s what gives me hope.”

Knowing more about the ugliest parts of our country’s history doesn’t have to be a constantly shame-inducing experience for white Americans. What it can do is inform the way we think and act when it comes to forging the path ahead.

Cruz’s noxious comments serve as a reminder: We can choose to learn more about how our past drives our present — and how we can make it better serve our future. Not in spite of a disgraceful senator’s insulting speech. But because of it.