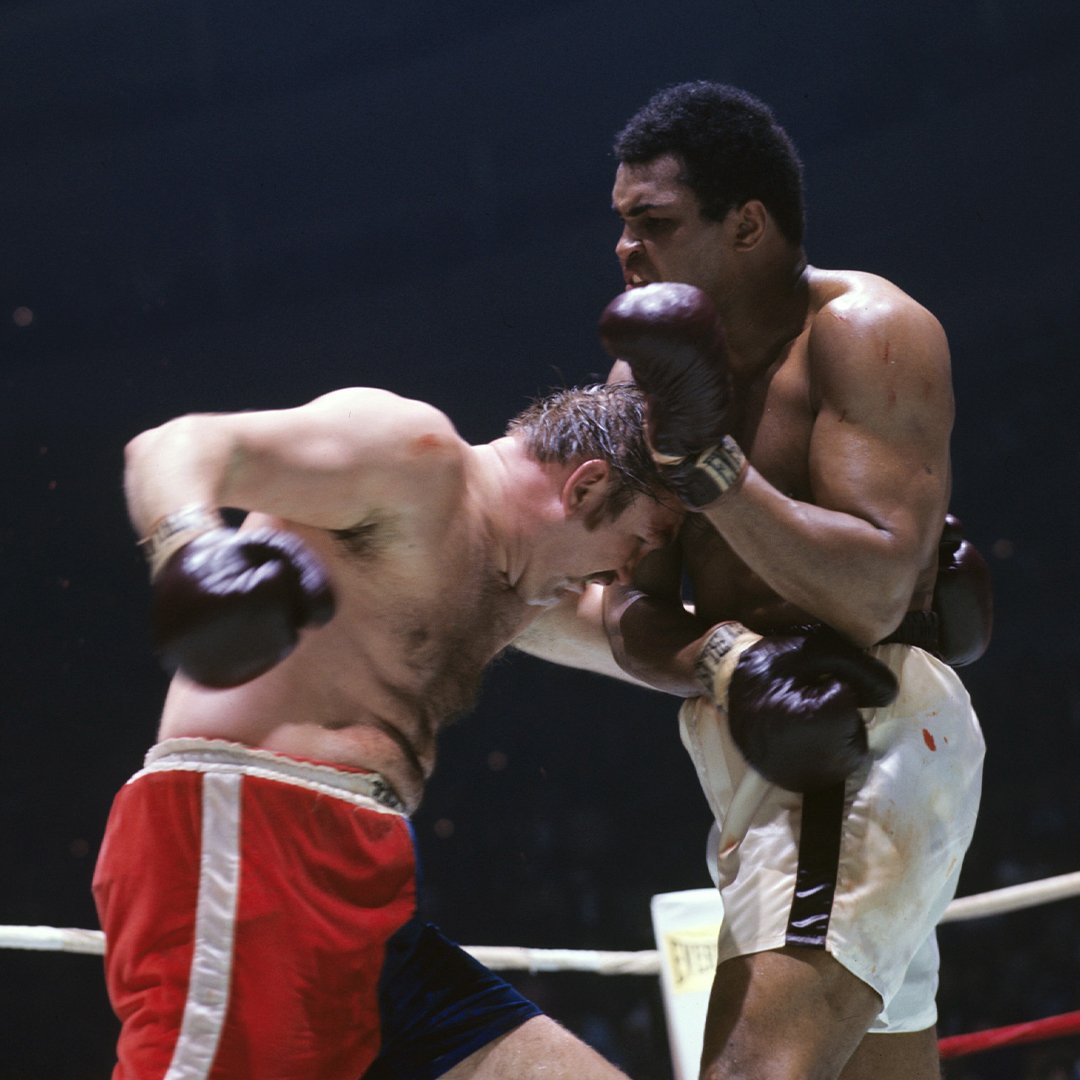

One of his boxing trunks was blue, the other red, and a white waistband wrapped around his skin. He looked all-American as he moved around the ring. The only problem was that his nose was broken and he was leaking blood from a severely cut eye.

You might think I’m describing “Rocky Balboa.” But I’m not. This was a real boxer, a New Jersey journeyman named Chuck Wepner. In 1975, Wepner had been guaranteed $100,000 to fight Muhammad Ali, who was to get $1.5 million. Don King needed a white fighter, and the the 36-year-old known as the “Bayonne Bleeder” — for his propensity to take punishment as he dumped fluids onto the canvas — got his chance at the title. His record was 30-9 at the time, and he’d had more than 200 stitches over the course of his career.

Though Wepner was a 30-1 underdog to not even get through the first three rounds, he didn’t see it that way. He talked about the fight as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity:

“This is my shot at the pie in the sky, the brass ring, the heavyweight championship of the world. I’m not going to blow it.”

When they rang the bell that night inside Cleveland’s Richfield Coliseum, Wepner came out swinging and shocked everyone by winning the first round. Ali then became more serious and took the next two. But Wepner had already beaten the odds by making it past the third — and he wasn’t done.

With one minute gone in the ninth, the announcer described the condition of the challenger:

“We’re beginning to see the blood spurting across the eye of Chuck Wepner.”

But exactly twenty-five seconds later, Chuck Wepner landed a clean punch to Ali’s left ribs — and knocked the champ to the canvas. It was bedlam in the Coliseum!

Ali got up, and the match kept going. And the Bleeder kept bleeding. But he also kept fighting. James Brown, who’d visited the announcer’s booth for a round, was nearly in tears:

“I see it but I don’t believe it. Ali has thrown everything at him that you can throw at him. And he’s still on his feet and getting a big round of applause from the people in this building. It’s unbelievable.”

Chuck Wepner took Muhammad Ali all the way to the 15th round, where the referee called the fight for the champ with 19 seconds left. The night before the fight, Wepner had said to his wife: “Even if I don’t win, I just wanna prove I belong there.”

After the fight, Ali confessed that Wepner had actually given him a better fight than ranked contender Ken Norton had. He also mentioned the crowd’s reaction:

“He fooled you all. He had you all rootin’ for him at the finish.”

People love any underdog that surprises — especially if they display true heart and courage. It’s a pretty universal theme. And the spectators could feel it that night, including a struggling 29-year-old actor named Sylvester Stallone. We’ll get back to him shortly.

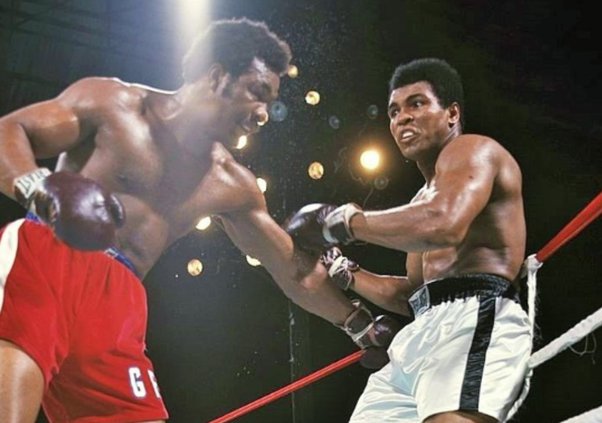

In the prime of Muhammad Ali’s career, he was the target that other heavyweight fighters wanted to knock off to become champion of the world. All elite boxers need to have a surplus of confidence to get where they want to go, but Ali’s boastful poetry took it to a whole new level. And he usually backed it up. But there was one famous fight where Ali was the underdog — and it was he who had to dig deep and find another gear, or some feared he might even end up dying in the ring.

The “Rumble in the Jungle” took place just six months before the Wepner fight, in Kinshasa, Zaire (now known as the Democratic Republic of Congo). Ali was trying to regain the heavyweight belt from George Foreman, a massively strong champion who had been pounding challengers into submission like a jack hammer.

Ali faced 4-1 odds to beat Foreman. But more than that, his fans and trainers were actually worried about his health. The mood in his locker room before the fight was so grim that Ali had to start psyching them all up before he headed to the ring! The historic match and its months-long lead-up in the Congo were documented in the 1996 Oscar-winning documentary, When We Were Kings.

In the first round, Ali shocked Foreman and all of the boxing experts by throwing a “right-hand lead” at the champ. A right-hand lead is hardly ever thrown by top boxers, because it gets thrown like a jab, without countering, and it also has to travel extra distance across the shoulders. Because of this, any fighter who throws a right-hand lead risks being open and vulnerable to getting a big-time tag back.

Ali didn’t tell anyone he was going to throw this punch, not even his own team. And he threw another 11 right-hand leads in the first round in an effort to score an early knockout. But while he caught Foreman off guard, all it did was make him angry. Or angrier. Foreman began whaling on Ali. It was brutal. “The Greatest” was in trouble.

Famed American writer Norman Mailer, who was on hand in Zaire and based a book on the fight, described the moment:

“Ali went back to his corner. The nightmare he’d been awaiting him in the ring had finally come to visit him. He was facing a man whom he could not dominate, who was stronger than him. Who was not afraid of him. Who was gonna try to knock him out, and could punch harder than Ali could punch. And this man was determined and unstoppable. And Ali had a look on his face that I’ll never forget. It was the only time I’ve ever seen fear in Ali’s eyes.”

Mailer said that Ali then began nodding to himself, as if he’d figured it out, and turned to the crowd and yelled “”Ali boma ye!” This was an expression in one of the Bantu languages spoken in the Congo that had come to mean “Ali, kill him!” And just as so many Africans had been saying those words as they followed Ali around in the run-up to the fight, now 60,000 live spectators started yelling it back to him. “Ali, boma ye! ALI, BOMA YE!”

The Rumble in the Jungle is where Ali first started using his famed “rope-a-dope” strategy. For the next seven rounds, Ali leaned back on the ropes and let Foreman swing away. Sportswriter George Plimpton, who was only feet from the ring, could hear it all in real time:

“Ali kept talking to Foreman: ‘George, you disappoint me, you don’t hit as hard as I thought you would. George, you’re not hittin’ hard enough!’ Foreman got angrier and angrier and in the middle of the fifth, he had punched himself out. He was exhausted. And that’s when Ali starts punching back and connecting. The crowd goes nuts.”

Ali knocked George Foreman out in the eighth round, in what is now considered to be one of the greatest sporting events of the twentieth century. It was a fight that hardly anyone thought Ali would win, and even he may have had his doubts after that first round.

I love those two boxing stories. I even watched the Wepner fight as I was writing this. Becoming the best in the world in any individual sport is indescribably difficult. But pro fighters confront pain and risks like no other. And whether you’re a figure that most may forget, like Chuck Wepner — or you’re a legend in your own time like Muhammad Ali — there are moments when we see these guys trying to find something deep, deep inside themselves in order to make the most valiant effort possible.

This principle applies to all of us at some point in our lives; it’s just the challenges and circumstances that differ. Which brings me back to Stallone. As soon as he saw the Bayonne Bleeder surviving Ali’s blows, round round after round, he knew that it was an epic, touchstone story. He went home and started writing Rocky.

Stallone actually had his own moment of truth after he wrote the movie. Paramount kept offering higher sums of money to him to sell them the script — but only if he would agree to not to play Rocky in it. The studio ultimately goosed the number up to $265,000, but Stallone knew that this was his shot. A few years later, he explained why he wouldn’t throw it away:

“I knew that if I’d have sold it, even for half a million, I knew that after the money was gone I would have become very bitter for having sold out. Because my one love was to at least fail on my own terms. I wanted to see if I could act.”

Paramount let him act. Rocky came out a year later and won the Oscar for Best Picture. The rest is Hollywood (and boxing) history.

Anyone can do anything.